Love as Moral Luck

This essay was originally published by Eli Parra on his blog.

My challenge here will be to distill for you a transcendent essay by Zadie Smith that changed my life in many ways, starting with making me read the massive novel from 1871 that it’s about. I’m writing this for you but also for me, because I need constant reminding of its unique message.

️ MAP OF THE ESSAY

️ PREAMBLE

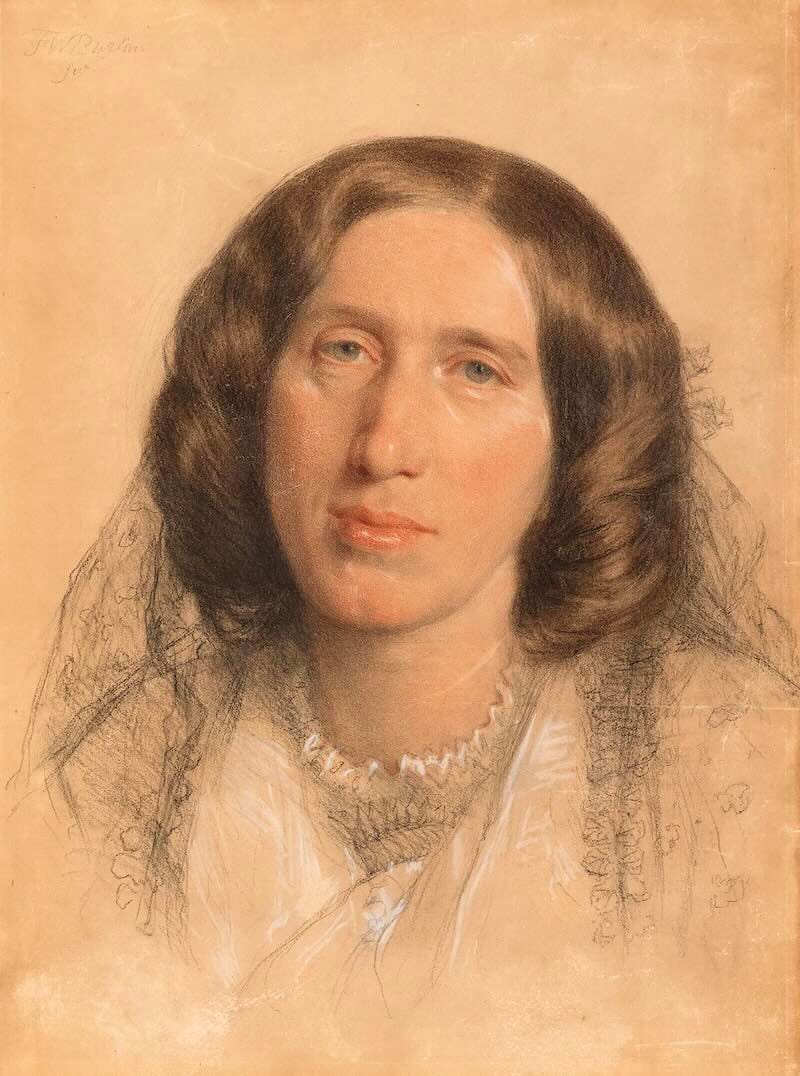

George Eliot and Zadie Smith

Smith, a major British novelist, published her long essay in The Guardian in 2008 with the title of The book of revelations, but it’s no longer online due to copyright issues. I know the piece from its appearance in the compilation Changing my Mind, where it has the title Middlemarch & Everybody.

In almost 5 thousand words, Smith defends George Eliot’s Middlemarch from the criticism by Henry James that of the 3 love problems in the novel, that of Fred & Mary is far inferior, the “least edifying.” It’s a relationship that “would seem more suited to a penny-farthing romance” instead of the most acclaimed English novel ever. Smith’s defense unfolds slowly, leading us through Spinoza, whose philosophy deeply impressed Eliot as she translated him into English.

I will not even go into Middlemarch’s brilliant but famously sprawling plot, only to say that the two other love problems involve the characters of Dorothea & Casaubon, Lydgate & Rosamond. My plan is instead to recapitulate some key passages of Smith’s argument, reweaving it around the idea of luck, which is how I’ve internalized it. The emphases in the quotes ahead will be mine, often on phrases that have become part of my inner monologue.

Also, while the essay centers on romantic love, the argument easily transcends it to include many kinds of love, including that of friendship.

LUCK

I tend to dislike the word luck because I contrast it with agency, which I revere. On my good days, I like to think of myself as in charge of my destiny, carefully planning & decisively authoring my fate by myself. Normally the most my controlling side can admit to is that we can make our own luck. On the opposite end of the spectrum, someone I know of once hit it big in a real-estate flip and would often proclaim this version of a local saying: “God, give me luck rather than intelligence.” That mock prayer both fascinates & horrifies me.

Why moral luck?

We’ll be talking about a unique kind of luck here, one that’s rarely talked about. Modern tech culture obsesses with the financial windfalls of FU money, generational wealth & fatFIRE, but what about the luck of who you’ll make a life with? Money is fungible but people are not: different people will draw out vastly different lives out of you. I chose love as moral luck for the title of this essay because this beautiful phrase from Smith still shocks me every time I read it:

Fred has no idea what he is capable of. His moral luck is all encounter, arrangement, combination. Mary Garth is that encounter; she is Fred’s reason to be good. It is through her, and for her, that he is able to change.

What could it mean to be morally lucky? The phrase is arresting because we usually think of morality as a system, logical & fixed, the opposite of something as chaotic & contingent as luck. But Smith argues that Spinoza & Eliot are both for a morality that springs from our own specific natures & our relationships, thus the chaos & contingency.

From Spinoza, Eliot took the idea that the good we strive for should be nothing more than “what we certainly know will be useful to us,” not a fixed point, no specific moral system, not, properly speaking, a morality at all. It cannot be found in the pursuit of transcendental reward, as Dorothea believes it to be, or in one’s ability to conform to a set of rules, as Lydgate attempts when he submits to a conventional marriage. Instead, wise men pursue what is best in and best for their own natures.

Luck as a demanding audience

In one of my favorite paragraphs in all of Middlemarch, George Eliot herself says:

Even much stronger mortals than Fred Vincy hold half their rectitude in the being they love best. ‘The theatre of all my actions is fallen,’ said an antique personage when his chief friend was dead; and they are fortunate who get a theatre where the audience demands their best.

We need moral luck because it is through others and for others than we can be our best selves. It matters who we find and who we surround ourselves with, because they can call forth the best in us. What could be luckier than that?

Luck as a path to kindness

This idea of moral luck also helps me be kinder with myself and others, because luck can be fickle. We can be spectacularly wrong in our judgements of what will be good for us. We need to forgive ourselves for having taken the wrong bets, dust off and try again, attending to our true nature.

of all the people striving in Middlemarch, only Fred is striving for a thing worth striving for. Dorothea mistakes Casaubon terribly, as Lydgate mistakes Rosamund, but Fred thinks Mary is worth having, that she is probably a good in the world, or at least, good for him (“She is the best girl I know!”) – and he’s right. Of all of them Fred has neither chosen a chimerical good, nor radically mistaken his own nature. He’s not as dim as he seems.

It’s also one of the strongest themes of the novel to extend sympathy for those unlucky enough to never find the company were they would flourish. Right in the prelude of Middlemarch Eliot asks us to see the potential 🦢 cygnet in each of us, forever hidden by circumstance:

Here and there a cygnet is reared uneasily among the ducklings in the brown pond, and never finds the living stream in fellowship with its own oary-footed kind.

“There but for the grace of God go I” is a useful call for humility to temper an extreme meritocracy that would suffocate you & others. You are deserving and you have strived, but you could have simply been unlucky to misjudge your nature and that of others.

Luck as a path to gratitude

Turns out moral luck was itself also how Mary Ann Evans became George Eliot, “that wisest of writers”. What follows I gleaned from Rebecca Mead’s delightful My Life in Middlemarch.

First, Eliot had the moral luck of having a father she “adored” and which inspired “the noble-headed, practical-handed artisan” which was “a recurring type” throughout her novels, even if “sometimes found too good to be true” by critics. In Middlemarch that type is represented by Caleb Garth, Mary’s father, a character that I don’t find implausible at all since he reminds me so much of my own father.

But above all was Eliot’s moral luck in meeting George Henry Lewes. While their union was scandalous at the time because George had a former marriage, posterity is brimful with admiration for the couple: they’ve been called “Victorian England’s one true marriage”, “a model of coupled contentment”, “as happy together… as any two people I have heard outside of outside of fantasy literature.”

The infamously unattractive Eliot met Lewes at age 32, late in life for Victorian standards and after much romantic disappointment. Eliot’s writing prior to her meeting Lewes showed brilliance but “does not yet manifest the large, perceptive generosity that characterizes the authorial voice of Middlemarch.” On the contrary she could be scathingly unkind, slashing:

It’s oddly reassuring to know that before she grew good, George Eliot could be bad —to realize that she, also, had a frustrated ferocity that it gratified her to unleash, at least until she found her way to a different kind of writing, one that allowed her to lay down her arms, and to flourish without combativeness or cruelty.

It was Lewes who encouraged her to finally write fiction, which Eliot in her bitter, priggish youth had renounced (“Have I any time to spend on things that never existed?”) Himself a writer, he was her first and best reader, never jelous and always encouraging. Biographers agree that he was “indispensable” to Eliot. “The sense of grateful, joyful indebtedness was mutual.” In her journal she wrote about him: “How I worship his good humour, his good sense, his affectionate care for everyone who has claims on him!” He wrote in his journal recalling their first acquaintance: “To know her was to love her.” It was through him and for him that Eliot wrote.

Middlemarch mostly concerns itself with the problems of young love… But the book was nurtured by love that was arrived at late, and cherished all the more for its belatedness.

The manuscript of Middlermach has the dedication: “To my dear Husband George Henry Lewes, in this nineteenth year of our blessed union.”

Luck as a spur to action

Finally and most important for me, the idea of luck short-circuits my overthinking and calls me to action, to experiment: I just do not know beforehand who I can be with the right people. It makes me see the need to put myself out there into the world, to reach out, to avoid my tendency to withdraw and ruminate. There are more people out there in the 21st century than there will be seconds in my life.

What Fred surmises of the good he stumbles upon almost by accident, and only as a consequence of being fully in life and around life, by being open to its vagaries simply because he is in possession of no theory to impose upon it.

Here, finally, is the path that Spinoza & Eliot show us to moral luck:

[The wise] think of the good as a dynamic, unpredictable combination of forces, different, in practice, for each of us. It’s that principle that illuminates Middlemarch. Like Spinoza’s wise men, Eliot’s people are always seeking to match what is good in themselves in joyful combinations with other good things in the world.

PUSHBACK

Recently I had interesting pushback on this essay from a friend: “isn’t it healthier, more noble & more stable to be good for it’s own sake, for only one self?”, they asked. “Isn’t this dependence on others fragile, maybe even co-dependent, at its worst toxic?” Perhaps, I answered, but it’s also beautiful & inspiring that we all need each other to be who we could be.

Yet their reaction baffled me because it seemed like an extreme distortion of the subtle & fragile message of both Smith & Eliot. Keep in mind too that it took Smith 5,000 words to make her case & Eliot over 900 pages —assume that the ungainliness of this message is the product of my amateurish squeezing</. But I’m also reminded of Scott Alexander’s notion that we need (differing) extreme messages to counter-balance our (differing) extreme biases:

Some people really need to hear the advice “It’s okay to be selfish sometimes!” Other people really need to hear the advice “You are being way too selfish and it’s not okay.”

It’s really hard to target advice at exactly the people who need it. You can’t go around giving everyone surveys to see how selfish they are, and give half of them Atlas Shrugged and half of them the collected works of Peter Singer.

So take my obsession with this essay & this novel with a grain of salt. You may not need or profit from all this theory but it brought me to practice, the way that Smith says Spinoza did for Eliot: “it was theory that brought her to practice.” I hope it helps you. It has helped me, counterbalancing my perhaps extreme tendency to retreat into work & monkish joys, snapping me out of my anxious tendency to prefer the predictable if sterile security of loneliness to the possible pain of unlucky company. I treasure the essay because it challenges me to look for the best in me and to look outside for the best for me.

CODA

So how has this essay affected my life? I read it in 2018 and the year after it gave me the impetus to finally tackle the 900-page project that is Middlemarch, one of the most remarkable readings of my life (and yes, I drenched the whole book in my notorious highlighting). No novel has ever increased my sympathy & fellow-feeling more, connecting me to the actual people around me —it was like a major personality upgrade, a permanent boost in agreeableness. Through the years the essay & the book have prompted many lively discussions with friends & family. But most importantly, they have been a key motivation & guidance to my attempts at connection since, some of which turned out, luckily, to be spectacularly successful.

In the early post-pandemic days of November 2021 for example, I travelled to Mexico city to take a chance on an ultra-niche meetup where I ended up meeting Jon. At the start we didn’t know if we’d ever see each other again and we stayed in touch haltingly, but the friendship took —I kept being surprised over and over by his kind & cheerful spirit. After 2 years of weekly calls and a trip to

Puerto Vallarta this year, he is now my best friend and I’ve come to love him & his friends. Together we’re part of an emerging ultra-niche scenius (collective moral luck!) that calls forth the best in us.

Now I’m in Mexico city again, taking a chance at Interintellect’s first Mexico city casual IRL. Wish me (moral) luck!