Engineer and the Saint

A Polish engineer’s pursuit to design the perfect spinning wheel for Mahatma Gandhi

Originally posted by Niloy Gupta on Substack. Shared with acknowledgment to Irene Karthik and Flick Hardingham for hosting the story of philosophy salon series, which motivated me to become a writer and take up such a challenging subject. Also Jason Crawford for inspiring in me the idea of a new philosophy of progress.

During the winter of 1931, Polish engineer Maurice Frydman (Maurycy Frydman-Mor), was in Paris in search of work during the Great Depression. He was at the Gare de Lyon railway station when he saw a large crowd gathering. A train pulled in, and a short half-naked man “all luminous and shiny as burnished gold” got down the train. The police were trying to control the crowd but the saintly figure stepped peacefully into the rabble to greet and bless them. Frydman experienced a “rapturous” and “mystical” experience. It was his first glimpse of Mahatma Gandhi, an apostle of non-violence and India’s eminent leader against the British colonial government. Such was the magnetic charisma of Gandhi that Frydman landed in India in 1935 to seek spiritual enlightenment. What was waiting for him in India was not just the life of an ascetic but the call of a humanitarian engineer, who would catalyze the Indian freedom struggle.

Spinning out a Revolution

The British government had a policy of economic exploitation of its colonies, particularly India. Cotton was bought at extremely low prices from India and then processed in the industrial mills of Manchester. The finished goods were sold at expensive prices in India. Britain’s industrialization was based on the premise of the deindustrialization of India. This policy of economic abuse was designed to keep Indians poor and subjugated.

Gandhi wanted to create a mass movement of boycotting foreign products in favor of locally manufactured goods. His strategy was to adopt the spinning wheel, a device for spinning yarn from cotton fibers, as a tool for making coarse cotton fabric or khadi. This would serve as a non-violent protest against the British textiles and create financial liberty for every individual. The idea was that Indians would feel a sense of empowerment, and self-reliance, and build up the courage to stand up against the injustices of the British Raj.

Gandhi championed the spinning wheel (Charkha) everywhere he went. Many photographs of that time show him in action at the Charkha, spinning Khadi. In order to make the Charkha accessible to the masses, he needed to make the process easy and efficient. After all, how can poor, untrained people compete against the highly mechanized mills of Britain? Gandhi, needed a light, portable spinning wheel which was efficient in spinning out cotton yarn.

The quest for an efficient spinning wheel

Maurice Frydman was living in Gandhi’s ashram when Gandhi put him up to the task. As an enterprising engineer, he hacked together an 8-spindle spinning wheel. Gandhi, the astute product manager, found it too complicated and requested something easy to use. After all, he was trying to drive mass adoption and user engagement. Just like with any Silicon Valley engineer today Frydman retorted that “a simpler spinning wheel won’t give you the output”. It is not easy to change the world and the visionary CEO will have none of the excuses.

Gandhi was persistent in his request for a simpler model. At that point in time, he had contrived ideas about market and labor economics. He did not care about output as he believed that the total work available in society was limited and static. If one person produced more than their share, others would be unemployed. Frydman was an engineer and capitalist at heart. He did not see eye to eye on economic matters with Gandhi. Nonetheless, he set about iterating on a perfect device to churn yarn from raw cotton fibers.

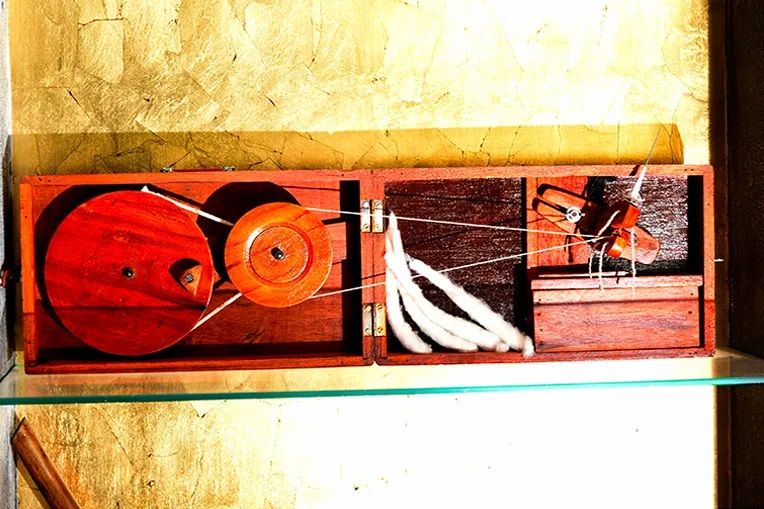

Over time he came up with the “peti charkha”. The peti charkha was a portable spinning wheel that folded into a contraption the size of a briefcase and could be carried with a handle. His final iteration was the “Dhanush Takli” which employed a bow and removed the wheel. It was 3x more efficient in spinning cotton than the traditional spinning wheel. By 1941 Gandhi evangelized this device in his writings and speeches. “The Dhanush Takli is more easily made, is cheaper, and does not require frequent repairs like the wheel… I draw a finer thread and the strength and evenness of the yarn are greater on the dhanush takli than on the wheel… if the millions take to spinning at once, as they well may have to, the dhanush takli being the instrument most easily made and handled, is the only tool that can meet the demand.”

Frydman’s inventions helped spark a mass movement. As hoped, the spinning wheel became an economic and political weapon against the British Government. The Charkha became a symbol of national resurgence and identity. It was adopted as a symbol for the flag of the provisional government of free India. The charkha on the flag was later simplified to the Buddhist’s wheel of life which represents unity and law. The spinning wheel continues to maintain its significance in India even today.

Poet versus Prophet

One of the notable contemporaries who criticized the Charka movement was Rabindranath Tagore, who was the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in literature. It was Tagore who gave Gandhi the title of Mahatma (great soul). In his essay the Cult of Charkha, Tagore argued that it was futile to compete against automation and industrialization. For India to progress, political leadership should embrace modern technology rather than fight against it. “If the cultivation of science by Europe has any moral significance, it is in its rescue of man from outrage by nature, not its use of man as a machine but its use of the machine to harness the forces of nature in man’s service.” He believed that India cannot break the shackles of poverty by embracing “undignified drudgery” of the spinning wheel. Tagore strongly believed that enticing millions of people to dedicate their time to a mundane task, would essentially kill individualism and creativity. “..it is an outrage upon human nature to force it through a mill and reduce it to some standardized commodity of uniform size and shape and purpose”. One might achieve political freedom but at the cost of enslaving the mind. Indians would be reduced to a “machine-like existence” and condemned to a “monotonous living death, burdened with a vocation that makes no allowance for variation in human nature”.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is easy to see that Gandhi and Tagore were both right and wrong in their foresight. It is tempting to call Gandhi a Luddite. Scott Fitzgerald is quoted as saying that “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” Gandhi certainly fit the bill. He was a clever politician, whose views evolved over time.

William Shirer, a famous American journalist and war correspondent of the time, observed that the first time a loudspeaker was used in a public meeting was at a Gandhi rally. Visiting the Manchester mills closed by the Indian boycott, Gandhi remarked on the low-quality machines and that it was not surprising that Japan was beating England. This sense of fluid economic thinking gets exemplified by his nomination of Jawaharlal Nehru, the great modernist, as his successor. Nehru was a vocal industrialist during his political career. He famously championed the slogan that dams, factories, and laboratories were the temples of modern India. Gandhi wanted to make the Charkha a symbol of resistance and not the only source of economic sustenance for India. He understood that India was a Janus-shaped entity, and wanted the modernists to recognize that in their quest for industrialization they do not leave poor rural India behind.

Gandhi tried to counter the charge of spinning yarn as a monotonous mind-numbing task. It was one of the reasons he requested Frydman to come up with something simpler. He attempted to make the activity engaging by composing songs and community spinning sessions. “Take to spinning (to find peace of mind). The music of the wheel will be as balm to your soul. I believe that the yarn we spin is capable of mending the broken warp and weft of our life..”. There is anecdotal evidence that yarn spinning is therapeutic. (There are Charkha spinning and meditation workshops in New York).

At the end of the day, it was grunt work. He slowly pivoted from the notion of spinning yarn throughout the day for a living to making it a leisure activity, where people contribute their free time to a national cause and express solidarity. His intention was to expand the scope from spinning yarn to making handicrafts and artisanal products. This would create a thriving rural economy, employing the creative faculties of the mind and dexterity of the body.

The Gandhian notion of handicraft is Heideggerian. In What is Called Thinking Martin Heidegger observed that the hand is different from all grasping organs- paws, claws, fangs. Only a being who can think and speak can have hands that can make the works of handicraft. Craft essentially means the strength and skills in our hands. The hand holds, carries, designs, signs, and folds in prayer. Heidegger adds: “All the work of the hand is rooted in thinking. Therefore thinking itself is man’s simplest and for that reason, hardest handiwork”. (It should be mentioned that Heidegger was a Nazi sympathizer. One must separate the idea from the man, just like wheat from the chaff, when trying to form an impartial opinion. After all, Aristotle strongly believed in and justified the institution of slavery.)

Gandhi’s vision of creating a rural economy that thrived on the local handiwork industry was never realized. While works of handicrafts do have artistic and aesthetic value, they could not compete against the scale of automation, marketing, supply chains, and labor cost. Currently, the Khadi industry in India is propped up by government subsidies and patronage from a small section of patriotic citizens.

It is safe to conclude that the spinning wheel served as an effective weapon against colonization but a poor strategy for economic upliftment. The irony is that today global fashion giants employ millions in South Asia as workers in garment factories. Textile exports play an important role in countries such as Bangladesh, which was part of British India, by serving as a major economic engine and raising living standards. The Charkha today serves as a symbol of nostalgia and is not a dogma that Tagore feared.

Frydman for our times

Maurice Frydman was born to a poor family in Poland in 1901. His father died before he was born. His mother pooled the resources to send him to study electrical and mechanical engineering. He came to India with his wife who unfortunately contracted typhoid and died within three months. Despite these hardships, he embraced a life of positive action. He became a spiritual itinerant and a humanitarian engineer working on innovative rural projects. He created a device to convert cornhusks into food for children and wrote a paper on how to make edible food from watermelon waste. His inventions range from perfecting the spinning wheel to the most enduring mud hut. Before joining Gandhi, he was also a successful professional, as the managing director of a state electrical factory in Bangalore, India. Frydman was also instrumental in drafting a constitution for the newly democratic state of Aundh. He died on 1976 in Mumbai, India. The books “I Am That” and “Maharshi’s Gospel”, authored by him, talk about his spiritual exploits.

We need more heroes like Maurice Frydman. We need the same spark of unity, empowerment, and dignity of labor that the spinning wheel ignited in millions. Gandhi championed the idea that “The greater the decentralization of labor, the simpler and cheaper the tools.” This is the key to the solution.

Can we leverage engineering innovation to decentralize an economic activity to tackle today’s pressing challenges? The computer, internet, and software already did that for knowledge work. The rise of outsourcing, off-shoring, and remote work is a testament to that. But can we decentralize an activity that recovers this pious union of mind, body, and heart?

I believe the opportunity today lies in indoor gardening. Can we have indoor vertical gardens that require little care and provide for large quantities of nutritious produce? Growing your own organic herbs and vegetables has the potential to create the same phenomenon as the spinning wheel. It will not replace mechanized farming and agriculture supply chain. It will certainly not solve world hunger. However, it will create a sense of self-reliance, dignity, and harmony. It will encourage people to eat healthily. Moreover, it will be a symbolic protest against government policies and industry practices that are ruining our health and our environment. Gardyn and AeroGarden, are examples of companies that make such devices. However, they are expensive and inaccessible to the masses. We need engineering innovation that makes indoor gardening “cheaper and simpler”, and we need political leadership which can champion it as a mass movement.

References

- Gandhi on Khadi https://www.gandhiashramsevagram.org/constructive-programme/chapter-04-khadi.php

- Mahatma Gandhi and his apostles. Yale University Press, 1993, Ved Mehta

- Carnival of Science, Shiv Vishwanathan, 1997

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/maurice-frydman-catalyst-change-nikesh-lalchandani/

- http://life-after-joining-ishayoga.blogspot.com/2014/09/maurice-frydman-his-life-story-your.html

- Spinning wheel in freedom struggle, Satish K. Kapoor, 1999