"dating" by Elaine Wang

Please enjoy this post, “dating,” by writer Elaine Wang, originally published on her Substack “manners & mystery.”

Starting November 7th, Interintellect community members can join Elaine for informal communal “group therapy” in her series, “Conversations on Self-Compassion” where we discuss a different topic related to self-compassion each month and how it can be applied in our lives.

Happy Reading!

—ii Editorial

Seeing this question brought up a lot for me as it did for many people. While I don’t want to pass moral judgment on dating as a whole endeavor, I think it goes without saying that the way we date is very problematic.

It’s easy to blame the apps. They present the illusion of abundance by constantly feeding us new people, so it can be hard to really focus on one person and give them the time and attention needed for a relationship to grow. On top of that, most apps encourage us to make fast decisions, which means judging people in ways that are admittedly superficial, which feels icky.

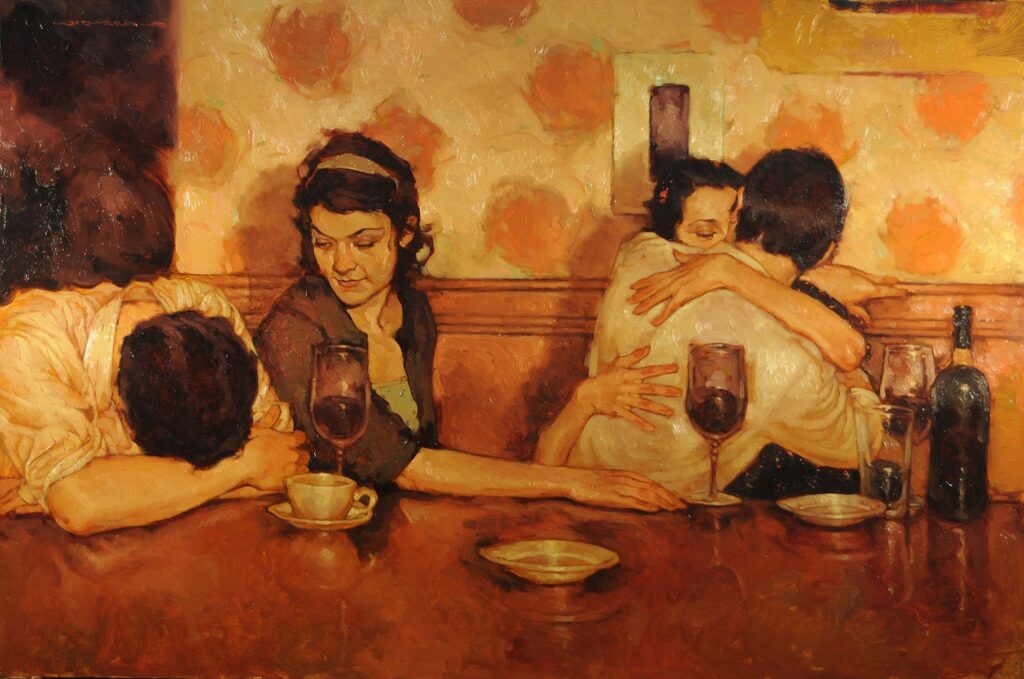

But I think the underlying problems are that (1) dating is a self-serving enterprise, and (2) it happens in private spaces. Courtship used to be conducted out in the open with lots of witnesses—family, friends, and neighbors all up in your business—and consequently, lots of gossip, so you had your reputation to look after. Modern courtship happens in the privacy of apps, DMs, and one-on-one interactions (no chaperones trailing you and your date through Central Park). As a result, it’s easy for bad behavior to go unchecked. While family might have some influence in who you choose to date, primacy is placed on individual choice. In love, as in all aspects of modern life, we’re encouraged to pursue our dreams. So in the process of trying to fulfill a deeply personal fantasy, we’re blindly wreaking emotional havoc on each other.

When it comes to matters of the heart we are encouraged to treat partners as though they were objects we can pick up, use, and then discard and dispose of at will, with the one criteria being whether or not individualistic desires are satisfied.

bell hooks, All About Love: New Visions

So much hurt is perpetrated that everyone thinks they have the right to be selfish—because isn’t everyone else just looking out for themselves? Chances are, people who ghost have been ghosted themselves. Anyone who has ever led someone on has also been led on. In most cases, it’s not intentional. Culture begets more of the same culture, and when we experience a certain behavior, when we hear about it from friends, from TikTok/Twitter/Instagram, it gets normalized. When we’re guilty of the same kind of behavior we complain about, we tend to think it’s O.K. because we’re able to explain why we did it. Our subjectivity allows us to justify it.

As someone who’s currently in the dating trenches, there are days when it’s a slog to open the app and respond to the conversations I have going because a part of me has already given up. I’m well aware of the dangers of my jadedness. It can lead me to behave in ways that are careless, that can unintentionally hurt others and cause them to put their guards up, to play games, be less trusting, more suspicious, more cynical, less sincere. And thus, the vicious cycle continues.

Instead of treating dating as a self-serving enterprise, what if we made a conscious effort to approach it as a joint venture? In Rethinking Sex, Christine Emba talks about “willing the good of the other” as a solution to make sex (and dating) less bad. If I want to sleep with someone, but I know that doing so might cause them to develop feelings I can’t return, I shouldn’t do it, even if they agree to it. Because it wouldn’t be right for them. At the very least, we should have a conversation about it. This is holding ourselves to a higher standard than consent. We can’t just do things that suit us even if there’s consent, we need to also consider what’s truly good for the other person.

It’s taking responsibility for navigating interactions that may seem ambiguous, rather than using that ambiguity as an excuse for self-serving “misunderstandings.” It would ask us to will the good not generally but for our specific partners in the moment we meet them. As a practice, it might look like radical empathy: imagining ourselves in the other’s stead and considering what they might feel about the encounter, not just in the moment but in the days to come.

Christine Emba, Rethinking Sex

This requires abundant communication. And not just, “What are you looking for?” but “What are you looking for with me?” One time, a guy and I talked about all the important stuff on our first date. We both wanted to find a long-term partner, get married, have kids, and travel. We even talked about how we would raise kids. We seemed totally aligned. And there was chemistry. Things moved quickly.

One of my flaws is that I am not direct. I prefer to keep my feelings to myself and wait to see where the other person is. Basically, I like keeping my cards close to my chest to avoid getting hurt. It rarely happens this quickly, but by the end of the second date, I’d totally fallen for him. I could envision a life with him. After a month and a half, I sensed him pulling back and realized I could either continue in a state of anxious speculation or I could be direct about what I wanted and see if he could meet me where I was. So I told him how I felt and what I wanted.

While his answer wasn’t what I was hoping for, it was the answer I needed to move on. As painful as the experience was, I learned an important lesson. Don’t just assume that someone who’s looking for the same thing as you is looking for that thing with you. Everything we did was 100% consensual, but that doesn’t mean it was right, that it couldn’t have been a better, more honest experience. Because I didn’t ask for clarity sooner, because I didn’t tell him how I felt about him, he made the convenient assumption that what we were doing was casual, that we were both keeping our options open. If he had considered how his actions might affect me, given what my goals were, the proper thing to do would’ve been to talk about where we were emotionally instead of proceeding as usual.

Emba’s rule can be applied to not just sexual encounters but any romantic situation. If I’m unsure how I feel about someone after our third date, I should let them know where I am so they can moderate their own emotional investment. I should be honest about what I like about them, what I’m unsure about, and where I want to go from there. It’s not an easy thing to do because being vulnerable is scary, but it’s the decent thing to do. I’m not advocating for returning to a time of chaperones and arranged marriages, but I do think a certain level of civility needs to be restored in dating, and it starts with the question of, “Is this good for me and my date?” If I’m unsure, we should talk about it. It’s not a trivial question with an obvious answer. We should interrogate what is good.