"153: Timeless Wisdom" by Jason Shen

Unpacking wisdom on solving problems, managing projects, telling stories, and driving movements that have stood the test of time.

Originally posted by Jason Shen on his website, on May 22 2023

Jason has an upcoming Interintellect salon on July 12th, be sure to check it out!

A little while ago, I tweeted about some of the timeless documents I come back to again and again. Stuff that has stood the test of time, and continues to be full of insight and relevant ideas. I initially came up with 4:

I didn’t go into detail in my tweet but in this newsletter, I’d love to share a bit more about each source of wisdom and why they matter.

Hope you are enjoying May—today’s my birthday which means next week is an annual lessons learned post!

What’s on deck this week:

- ⚡️ Have the courage to work on important problems (Hamming)

- 👁️ We admire characters for trying (Pixar)

- ⚙️ Rules for project managers: useful reviews & simple software (NASA)

- 🫶 A social movement’s battle for hearts and minds (Moyers)

⚡️ Have the courage to work on important problems (Hamming)

In Richard Hamming’s “You and Your Research“, one of the timeless pieces I come back to again and again, he talks about finding the courage to work the most important problems by focusing on your successes.

I began by asking what the important problems were in chemistry, then later what important problems they were working on, and finally one day said, “If what you are working on is not important and not likely to lead to important things, then why are you working on it?” After that I was not welcome and had to shift to eating with the Engineers!

Like many of us, these chemists were intimidated by the most important problems and wanted to avoid failure so they avoided them. But courage means knowing that failure is not the end of the world and that large-scale success is worth pursuing.

Confidence in yourself, then, is an essential property. Or if you want to you can call it “courage”. [Claude] Shannon had courage. Who else but a man with almost infinite courage would ever think of averaging over all random codes and expect the average code would be good? He knew what he was doing was important and pursued it intensely. Courage, or confidence, is a property to develop in yourself. Look at your successes, and pay less attention to failures than you are usually advised to do in the expression, “Learn from your mistakes”. While playing chess Shannon would often advance his queen boldly into the fray and say, “I ain’t scared of nothing”. I learned to repeat it to myself when stuck, and at times it has enabled me to go on to a success. I deliberately copied a part of the style of a great scientist. The courage to continue is essential since great research often has long periods with no success and many discouragements.

👁️ We admire characters for trying

In 2011, former Pixar story artist Emma Coates tweeted 22 nuggets of wisdom about telling stories that have been shared far and wide. But even if you aren’t a storyteller by trade, many of the lessons hold true for reality as much as they do in imagination.

In particular, the rules about character, growth, and pursuing what matters. Similar to Hamming’s advice about going after “the most important problems”, we admire characters that pursuing things that really matter to them, in the face of great struggle and discomfort, and we care less about whether they get it than if they tried.

What if we applied that same thinking in our own lives?

1: You admire a character for trying more than for their successes.

6: What is your character good at, comfortable with? Throw the polar opposite at them. Challenge them. How do they deal?

16: What are the stakes? Give us reason to root for the character. What happens if they don’t succeed? Stack the odds against.

⚙️ NASA’s Rules Project Managers (Reviews, Software)

I came across this list when I was graduating from college and every time I read it, I think I learn something new. Jerry Madden had a 35+ year career at NASA and retired as the Associate Director of Flight Projects so he knew a thing or two about managing ambitious, high-risk technical projects.

Madden shared a total of 122 rules covering everything from design engineering to people management, contractor relations, process and more. Here are a few that stood out this most recent time I looked at them:

🧾 On making the most of project reviews: the idea that the presenter is the one gaining the most out of a review is a brilliant point. With NASA projects, a single a mistake could cost millions of dollars and risk human lives, and reviews are one of the most important ways everyone builds confidence in the initiative.

Reviews are for the reviewed and not the reviewer. The review is a failure if the reviewed learn nothing from it.

External reviews are scheduled at the worst possible time: therefore, keep an up-to- date set of technical data so that you can rapidly respond. Having to update business data should be cause for dismissal.

Hide nothing from the reviewers. Their reputation and yours is on the line. Expose all the warts and pimples. Don’t offer excuses–just state facts.

💻 On avoiding mistakes with software: Madden spent most of his career working with physical hardware, with software being a more limited part of his toolkit. Yet the observations he offers are on point, especially the one about building a simple system that works before adding the bells and whistles.

Not using modern techniques like computer systems is a great mistake, but forgetting the computer simulates thinking is still greater

Knowledge is often confounded by test. Computer models have hidden flaws, not the least of which is poor input data.

Software now has taken on all the parameters of hardware, i.e., requirement creep, high percent-age of flight mission cost, need for quality control, need for validation procedures, etc. It has the added feature that it is hard as hell to determine it is not flawed. Get the basic system working and then add the bells and whistles. Never throw away a version that works even if you have all the confidence in the world the newer version works. It is necessary to have contingency plans for software.

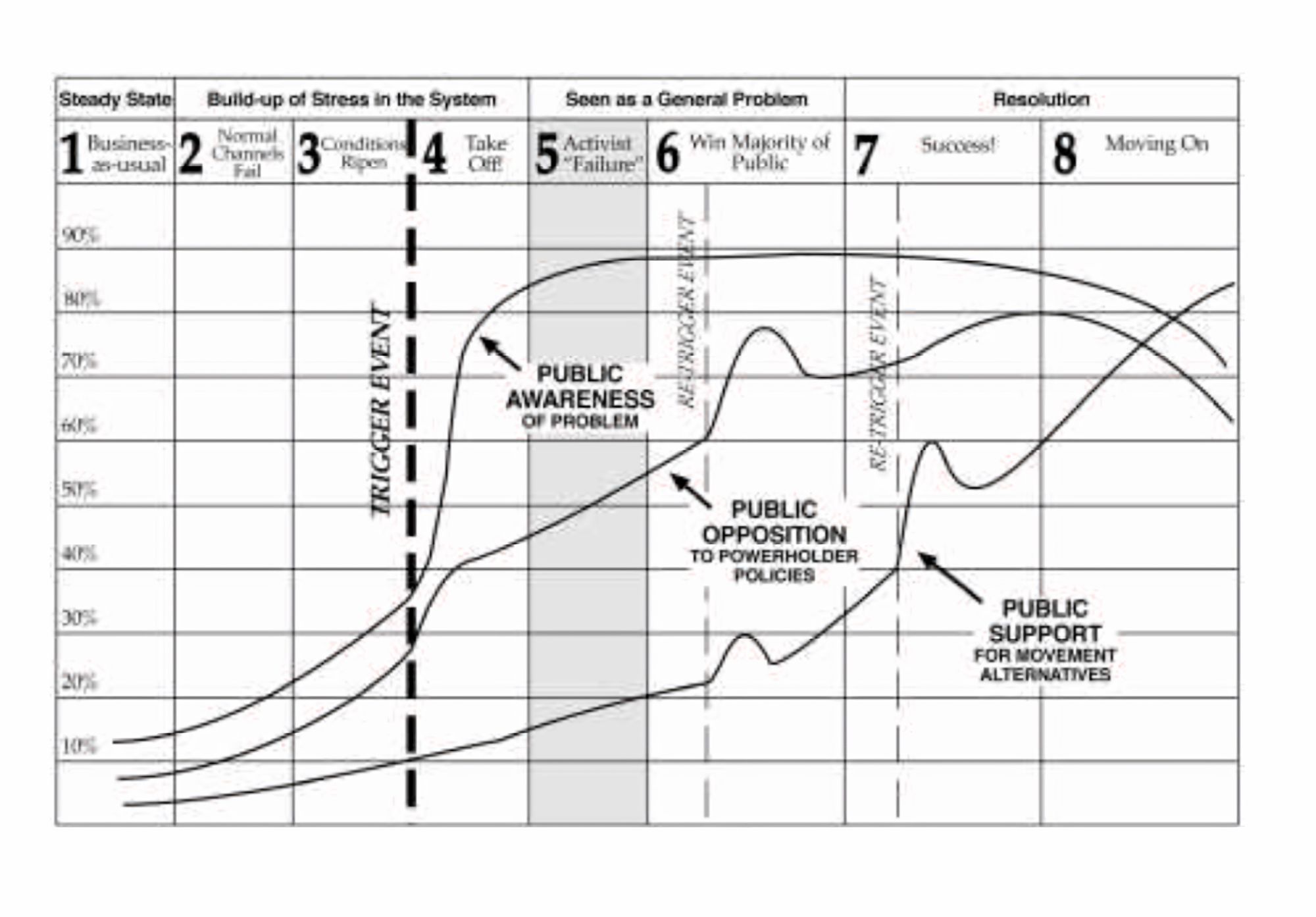

🫶 A social movement’s battle for hearts and minds (Moyers)

William Moyers (1933-2002) was an American change activist who was the principal organizer of the Chicago housing movement in the 60’s and went on to capture a powerful framework for thinking about how to drive social change. He includes the US’s anti-nuclear energy movement as a case study (which while probably correct for the time, now feels like it needs to be reversed) and even decades after he first developed it, still feels as relevant as ever for driving social change.

Symbolic actions and human values drive movements

The source of power of social movements lies in two human qualities:

– A strong sense of right and wrong. People have deeply felt beliefs and values, and they react with extreme passion and determination when they realize that these values are violated.

– We understand the world and reality, in large part, through symbolism.

The battle for the public

Moyers frames the central aspect of social change as a battle between the elite powerholders and the movement for the hearts, minds, and support/acquiescence of the general public. This makes it much like a political campaign, except over an idea rather than a person.

The powerholders advocate policies that are to the advantage of society’s elites, but often to the disadvantage of the majority population and in violation of its strongly held values. Before movements begin, however, the populace is usually unaware of the problem and the violation of their values, but they would be very upset and easily spurred to action if they knew.

Avoiding burnout among

Ultimately, the movement must prevail by achieving 3 objectives:

- Building awareness of a social problem

- Growing the public’s opposition to the powerholder’s policies

- Winning support for the movement’s alternatives.

Because each of these efforts take time, Moyers cautions that activists must avoid burnout when it takes longer than they’d like for the movement to achieve victory.

By the end of take-off, many activists suffer from “battle fatigue”. After two years of virtual ’round-the-clock activity in a crisis atmosphere, at great personal sacrifice, many activists find themselves mentally and physically exhausted and don’t see anything to show for it. Out of quilt or an extreme sense of urgency, many are unable to pace themselves with adequate rest, fun, leisure, and attendance to personal business. Eventually, large numbers of activists who were part of movement take-off lose hope and a sense of purpose; they become depressed, burn out, and drop out.